‘Shapes, plastic expression, art? The Plokker collection.’ by Liesbeth Reith

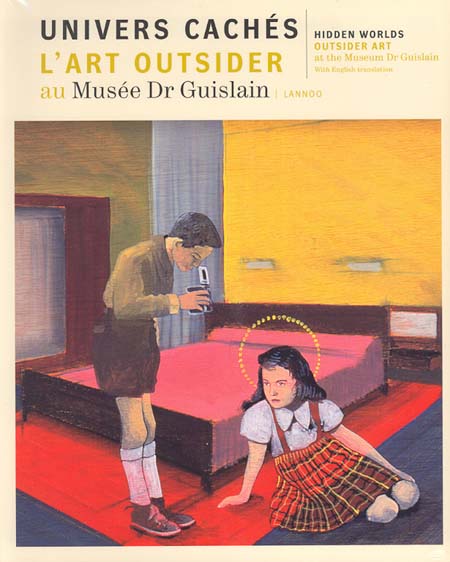

12.05.2018 PublicationsLiesbeth Reith wrote about Plokker’s theory: ‘Shapes, plastic expression, art? The Plokker collection.‘ in the publication Hidden Worlds. Outsider Art in the Museum Dr. Guislain, Ghent 2007.

A quote from her text:

“The psychiatrist Prof. dr. Johannes Herbert Plokker was one of the first in the Netherlands to set-up a studio for creative therapy. That was around 1955 in the institution ‘Hulp en Heil’. Himself a member of a group of painting doctors, he felt that creative development was extremely important. Plokker was engrossed by the revolutionary developments of modern art in the early twentieth century. He was fascinated by Hans Prinzhorn’s Bildnerei der Geisteskranken and thereby discovered that art by psychiatric patients was a rich source of inspiration for expressive and surrealist artists.

Plokker had an exceptional vision of creative therapy for the times. He mainly considered painting, drawing and modelling an occupational therapy that makes the patient active and gives him a feeling of still being capable of something. That reinforces his self-confidence. He held the opinion that this therapy cannot be used for the diagnosis of the illness. The content of a painting or drawing can however be an aid to discover powerful emotions, which the patient has difficulty verbalising, earlier. He also believed that the deterioration or improvement of the illness could be seen in the work. There were no books on art in Plokker’s studio. Everyone was free to choose their own subjects and materials. Any patient who enjoyed expressive work, whether he or she had any talent or not, was welcome. The supervisors, including Plokker’s sister Grace, usually had an artistic background but the intention was not to give the patients an art education. This free method, without a targeted treatment programme, was unique at that time in psychiatry. Colleagues from at home and abroad came to look.

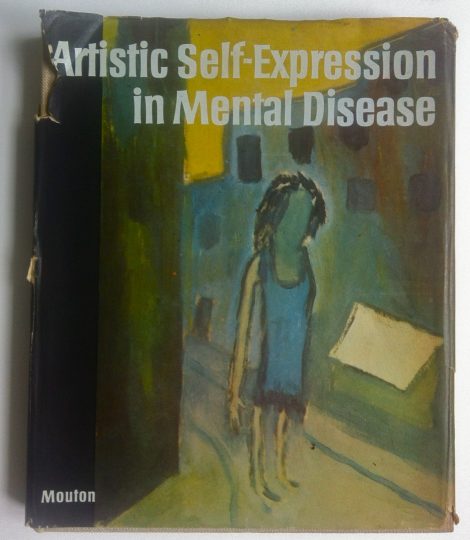

In 1962 Plokker published his thesis Geschonden Beeld: Beeldende expressie bij schizophrenen, a trade edition of which appeared in Dutch, French, German and English (as Artistic Self-Expression in Mental Disease: The Shattered Image of Schizophrenics).

The book opened with a number of considerations concerning schizophrenia, as background knowledge for the discussion of around ninety expressive statements of his patients in ‘Hulp en Heil’. Plokker hereby joins the discussion on creativity, which was then linked to psychological freedom. He wrote: ‘If one wants to include psychological freedom in the term ‘creativity’: a conscious choice and restructuration, then in most schizophrenics it will not or barely be possible to speak of creativity. Picasso could proudly say: ‘Je place les choses selon mes amours’, a schizophrenic patient cannot follow him in saying that.’ Plokker is thinking of the extremes here. Man is always limited in his psychological freedom. A life’s history and circumstances define the mode of expression and otherwise the physical and mental conditions do. Free will is an illusion.

‘The artist is an artist on the basis of his special ability intuitively to recognise shapes, symbolising emotions,’ says Plokker. In his opinion schizophrenics experience all kinds of things and events, which have no special meaning for normal people, as highly symbolic. For example, a chair may have two simultaneous meanings to a schizophrenic: an ordinary chair to sit on, but also a greatly loved grandfather. A viewer who does not understand these personal symbols, misses much of what the patient expresses in his work.

J.H. Plokker collected some 1100 works of art, while working in the mental institution ‘Hulp en Heil’ and preparing his thesis “Artistic Self-Expression in Mental Disease”, 1963.

Plokker considers Prinzhorn’s Bildnerei der Geisteskranken as a standard work, ‘although out-of-date in many points’. In the chapter Die Eigenart der schizophrener Gestaltung Prinzhorn maintains that in schizophrenics the forming process usually stops before the actual creation. In successful cases genuine artwork may be unintentionally created. Plokker supports this: ‘However True Art is much more than direct expression […] After all it required a certain form from those emotions!’ As a result Plokker does not want to call works by schizophrenic patients art, but does talk of ‘visual expression’, ‘creations’ or ‘shapes’. But to what extent did Plokker want to curry favour from his PhD supervisor from the psychiatric sector? At that time they generally held the opinion that schizophrenics were in any event incapable of creating art!”.